Around 1980 I stumbled upon the truth about Columbus in an old National Geographic magazine: “His greed awakened, Columbus demanded of each adult an annual tribute: enough gold dust to fill four hawkbells. Pay or perish. Many Indians fled, but the Spaniards tracked them down with dogs. Thousands ended their lives with poison. In 1492 an estimated 300,000 Indians lived on Hispaniola. By 1496 a third of them were dead. Less than a decade later the first black slaves arrived to take over the Indians’ oppressive burdens.” (Nov, 1975)

Fired up, I dug into the history and found out more of what had actually happened. I was so amazed that I wrote a play about it. With the help of friends, we staged a reading of an early version of The Trial of Columbus in a San Francisco book store in 1981. Then I wrote Columbus in the Bay of Pigs, a narrative poem about the conquest of the Caribbean, and published it in 1988.

in the Bay of Pigs

In 1990, the 500 year commemoration (1492-1992) was fast approaching, and the US Congress had declared the Quincentennial a national celebration, with San Francisco as the centerpiece. Replicas of Columbus’s three ships were sailing from Spain, scheduled to stop in various ports, and ultimately sail through the Golden Gate on October 12, 1992. The local progressive community was not yet very aware of it, but had to respond.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, replacing Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples Day had already been proposed over a decade previously, at a United Nations conference in Geneva in 1977, by the first Native people permitted to speak for themselves at the UN. The International Indian Treaty Council, recently formed at that time, had been instrumental in organizing this conference. The proposal however had never been followed up on.

In the spring of 1990 I met with Nilo Cayuqueo, a soft-spoken Argentinian Mapuche man with gentle eyes, director of the South and Meso-American Indian Information Center (SAIIC) on East 14th Street in Oakland. He had been a delegate at the 1977 Geneva UN conference. Together with other Indigenous organizations in Ecuador and Columbia, SAIIC was organizing The Encuentro: The First Continental Gathering of Indigenous Peoples on the 500 Years of Indian Resistance, scheduled for five days in July, in Quito, Ecuador. The spirit of the Encuentro sprang from an ancient Andean prophesy that when the tears of the eagle of the north and the condor of the south are joined, a new spirit will emerge, unite the Native nations, erase oppression, exploitation and injustice. Given Berkeley’s progressive history, Nilo suggested that we invite the mayor to attend, and if she couldn’t make it, ask her to send a representative.

Several weeks later I was in Quito, as Mayor Loni Hancock’s representative to the First Continental Encuentro. Indigenous Representatives from the Arctic Circle to the tip of South America were in attendance. A multinational Native meeting of this scope and magnitude had never before been attempted; it drew around 400 participants, with representatives from 120 different Indigenous nations, tribes, and organizations, as well as many NGOs. The conference ended with the Declaration of Quito, which affirmed “Our emphatic rejection of the Quincentennial celebration, and the firm promise that we will turn that date into an occasion to strengthen our process of continental unity and struggle towards our liberation.” Everyone promised to bring that message back home.

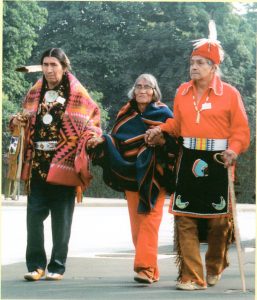

Upon return, Nilo and I reported to Mayor Hancock. Tony Gonzales from the International Indian Treaty Council, and Milie Ketcheshawno, who had been in the Alcatraz occupation, were there. Then the Bay Area Regional Indian Alliance organized an All-Native Indigenous Conference, attended by over 100, which on its final day moved to Laney College in Oakland, and opened to nonNative people. Over 300 people attended. In the end, we unanimously voted to “Declare and reaffirm October 12, 1992 as International Day of Solidarity with Indigenous People.” We formed an organization called Resistance 500, and set up local chapters, including Berkeley. The coalition quickly grew to over 85 groups, each planning events, and we met regularly at Inter-Tribal Friendship House. The Resistance 500 coalition made sure that the Quincentennnial hoopla had no support here, and the voyage of Columbus’s ships to San Francisco Bay was canceled.

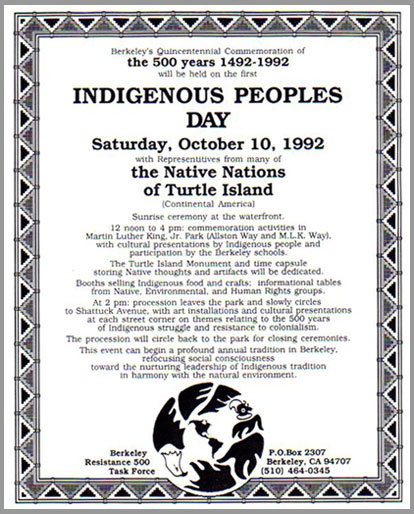

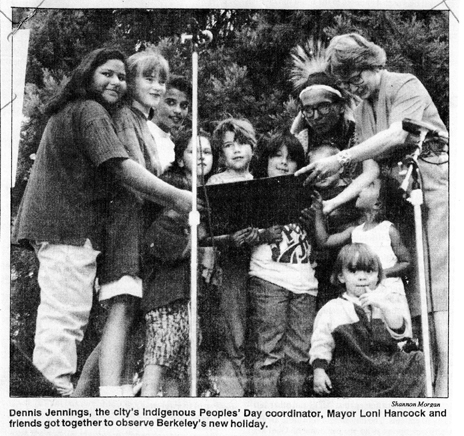

In Berkeley we approached the city, and the City Council gave us official status as the Berkeley Resistance 500 Task Force, with the mission of making recommendations on how the city should respond to the Quincentennary. We walked it through various commissions, until the City Council voted unanimously to make Indigenous Peoples Day an official Berkeley holiday beginning in 1992. We were the first city to declare it an official holiday, and for years the only city. With the support of the local Native community, we began holding our annual Berkeley Indigenous Peoples Day Pow Wow and Indian Market, which became a local tradition.

For years we remained the only city that celebrated Indigenous Peoples Day, but Berkeley showed how it could be done. Little by little word spread that it was doable on a local scale, town by town, city by city. Meanwhile the world’s consciousness was jolted by the environmental crisis, and growing numbers have been turning to Native wisdom for guidance. Today many millions around the country and around the world celebrate Indigenous Peoples Day and all that it means for preserving our planet.

There is much more to this history, and I have collected more of it in the book I curated, INDIGENOUS PEOPLES DAY: A Handbook for Activists & Documentary History

0 Comments