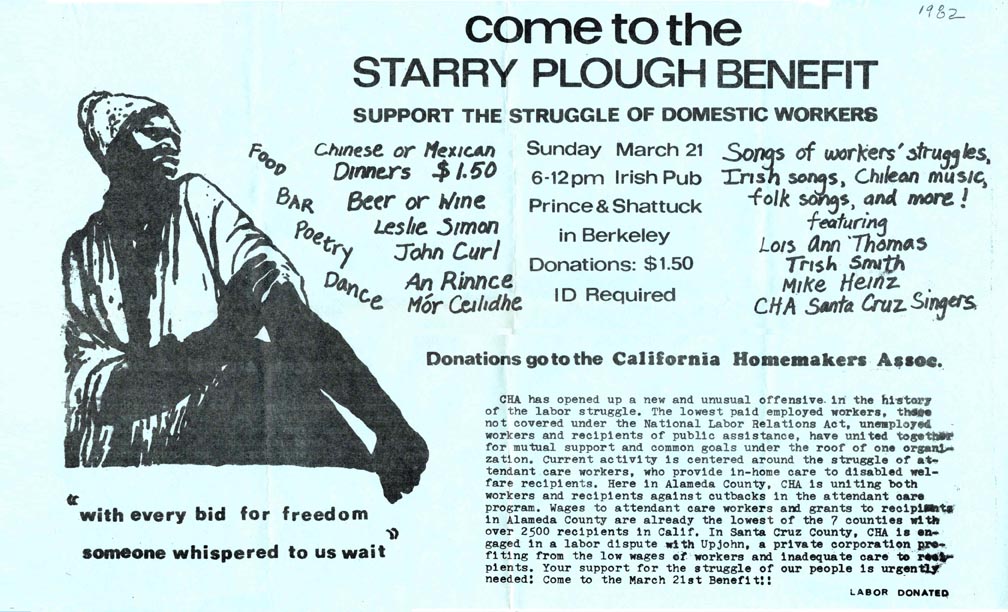

POETRY POSTERS, 1977-1982

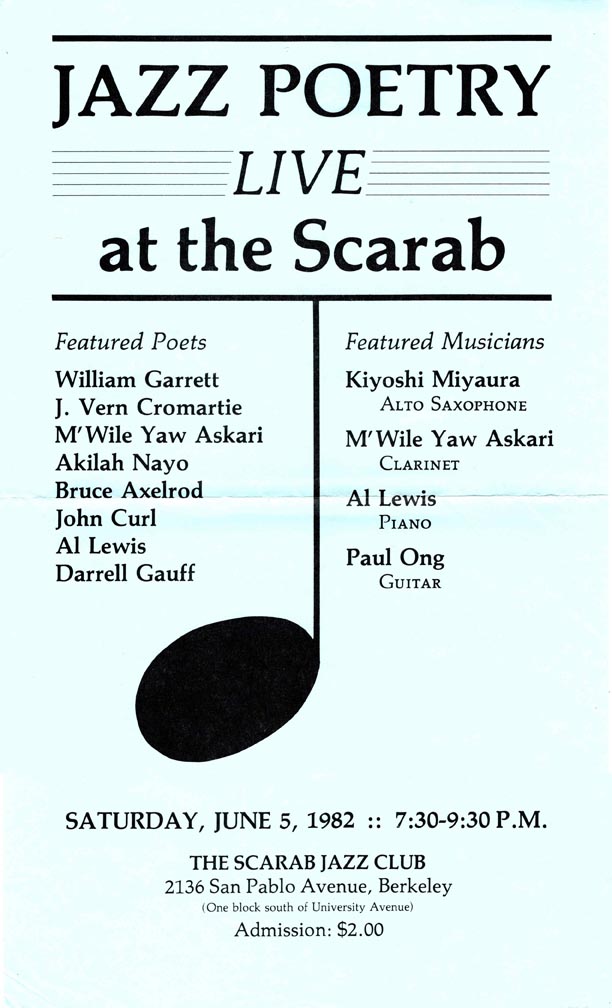

This is a series of over fifty poem broadsides that I printed, posted in public places, and gave away in the streets and at readings and in the San Francisco Bay Area during between around 1977 and ’82. Included in the collection are other artifacts from the time, including flyers for poetry readings and other events, programs, etc.

INTRODUCTION:

RADICAL POETS’ GROUPS IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1970s & ’80s

POETRY FOR THE PEOPLE, CLOUD HOUSE, the UNION OF STREET POETS and the UNION OF LEFT WRITERS

While I was posting my first round of WALL POEMS in the early 1970s, which I spray painted, silk screened and posted in public places, I also connected with the growing community of activist poets and writers in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Poets have always gathered in groups, and in those years many poets were inspired to get their work out into the community and to use the power of their poems to help change the world. Loose associations of poets were always forming and shifting, and I worked with three of them: Poetry for the People, Cloud House, and the Union of Street Poets.

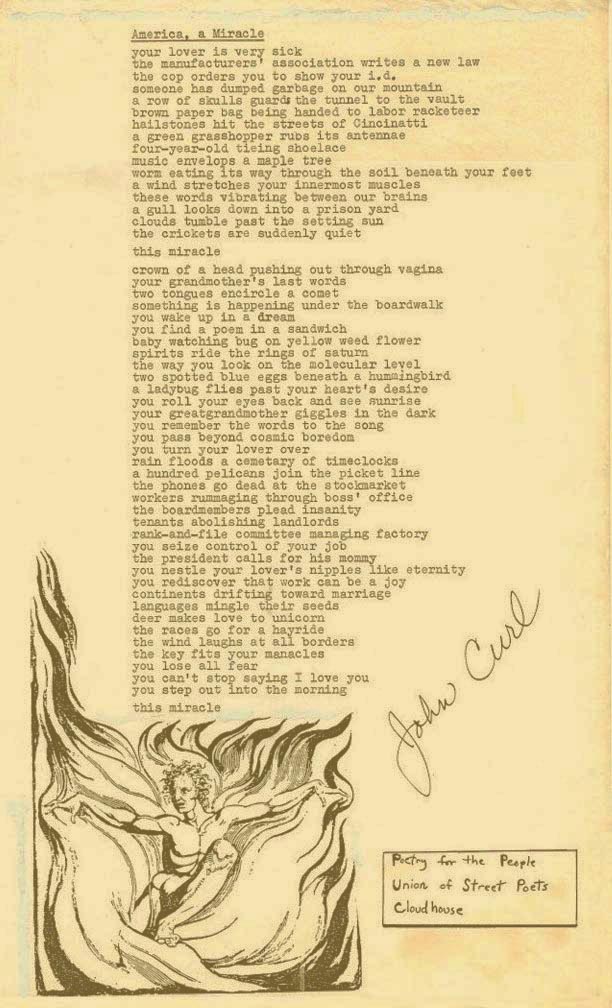

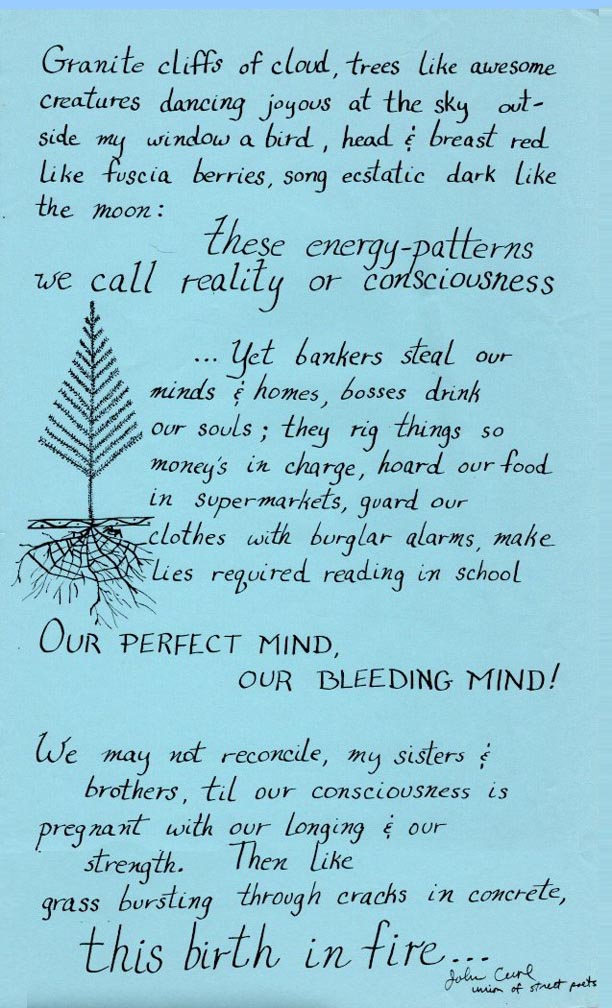

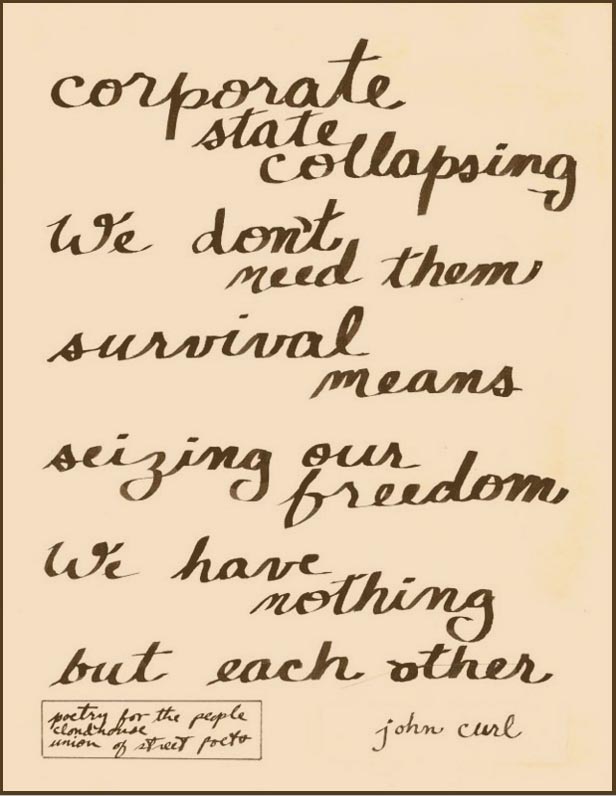

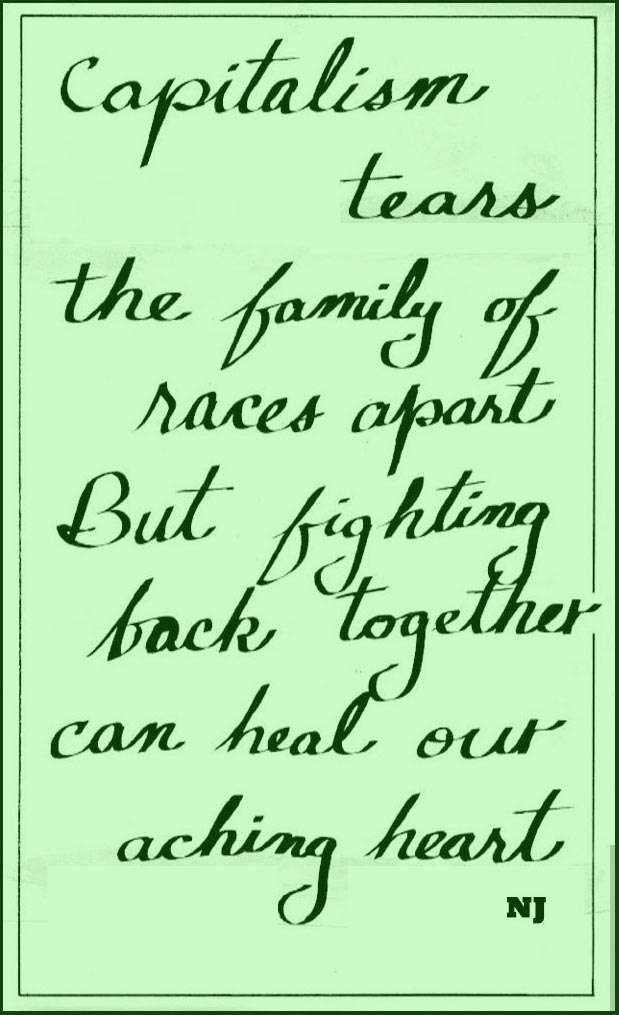

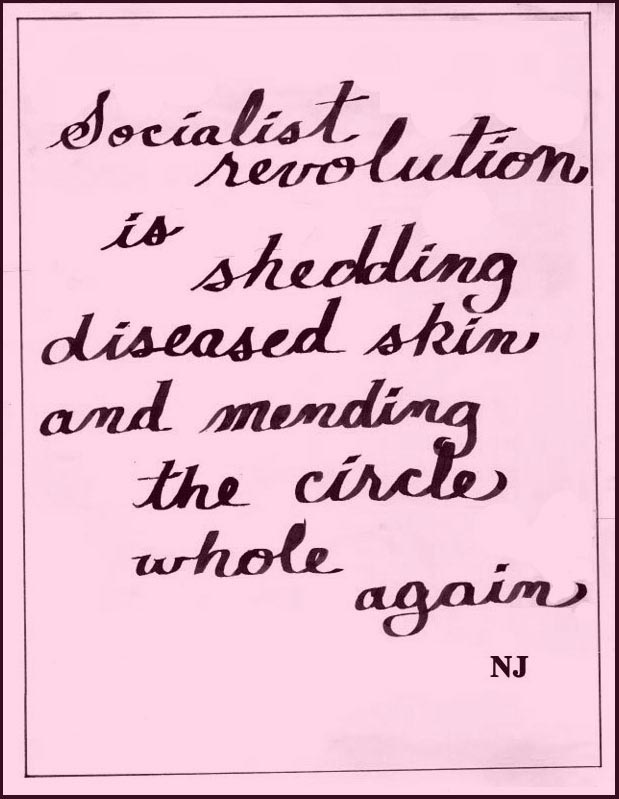

I launched a new series of over fifty poetry broadsides, posted them in public places and gave them away at readings. I signed some of these with my name, some as NJ, and left some unsigned. I usually added the name of one or more of the poetry groups that I was working with.

Poetry for the People (PFTP) revolved around the course that Leslie Simon taught at San Francisco City College beginning in 1975. Cloud House centered around the weekly poetry readings and poetry archive curated by Kush, starting in 1977. The Union of Street Poets (USP) was simply a concept that sprang from the minds of John Mueller and Jack Hirschman around 1980.

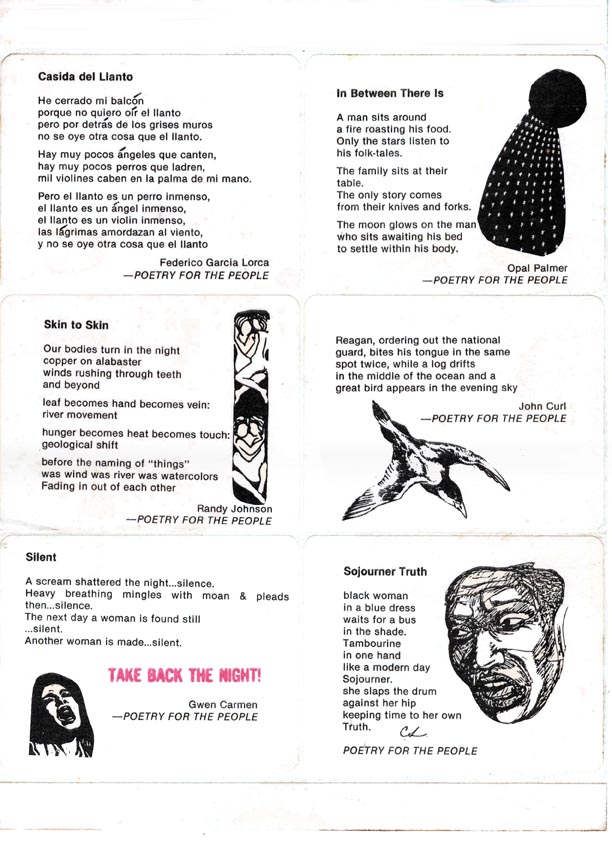

The groups were all loose collectives, each revolving around a different core, with overlapping members, created for sharing and distributing work, and other mutual aid. They were also banners of affiliation that poets could hang on their work. During those years, many poets printed broadsides and chapbooks under those mastheads. We all shared the vision of getting poetry out into the community, where it belonged, poetry for whoever walked by.

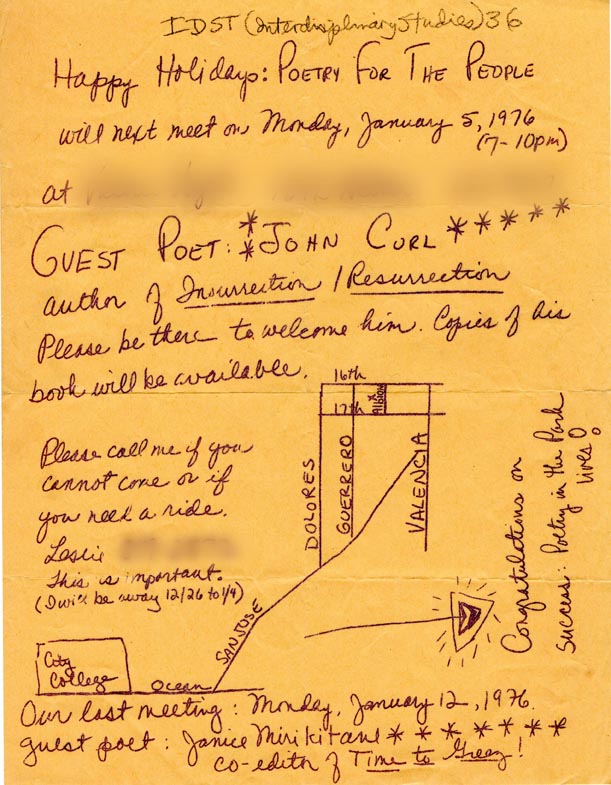

POETRY FOR THE PEOPLE

I knew Leslie Simon from East Bay poetry readings before she started Poetry for the People at City College in San Francisco in 1975. I was a guest speaker at her class in January, 1976, talking about my book Insurrection/Resurrection (1975), which contained my Wall Poems, and over the following years I participated in PFTP events and readings in public places. Leslie was an extremely good group organizer and instinctively understood the collective consensus processes that were becoming the organizing principles for progressives and radicals working together on the cutting edges of the cultural transformations of the time.

In 1978 PFTP published poetry stickers and an anthology, Pulse of the People.

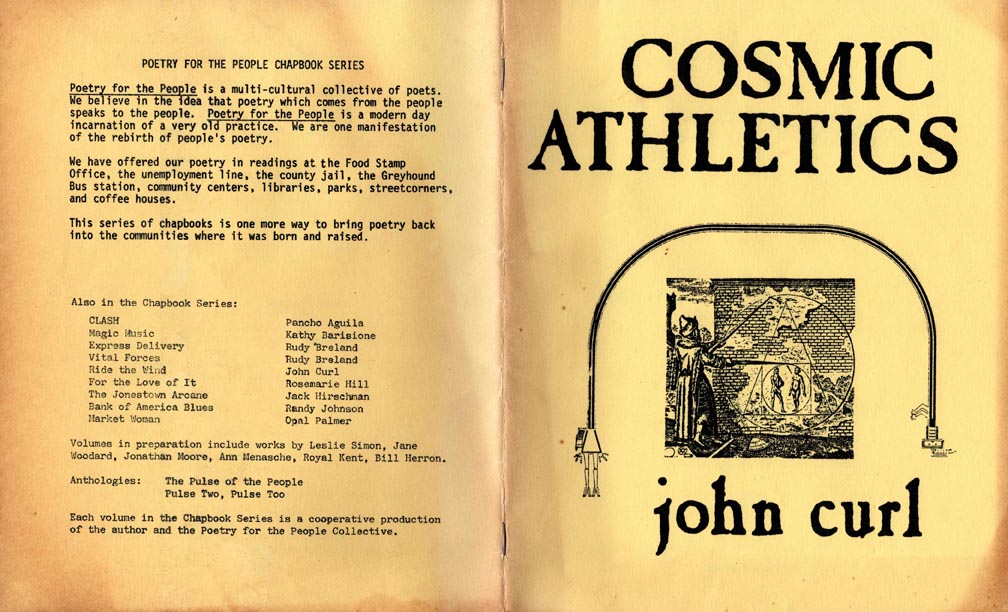

In 1979 the PFTP Chapbook Series kicked off with my book Ride The Wind, which consisted of a series of sixteen poems based on the tai chi that I was practicing at the time. The next chapbook we printed was Jack Hirschman’s Jonestown Arcane. The series included Pancho Aguila, Opal Palmer, Rudy Breland, Gwen Carmen, Clare Strawn, Leslie Simon, and others.

In 1980 I published a second chapbook in the series, Cosmic Athletics.

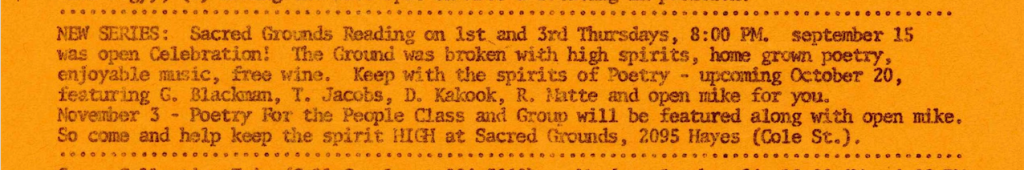

In 1977 I participated with the PFTP collective in some of the earliest readings in the open poetry series at Sacred Grounds cafe, which went on to become one of the longest-running open readings in the world, and today is still going strong.

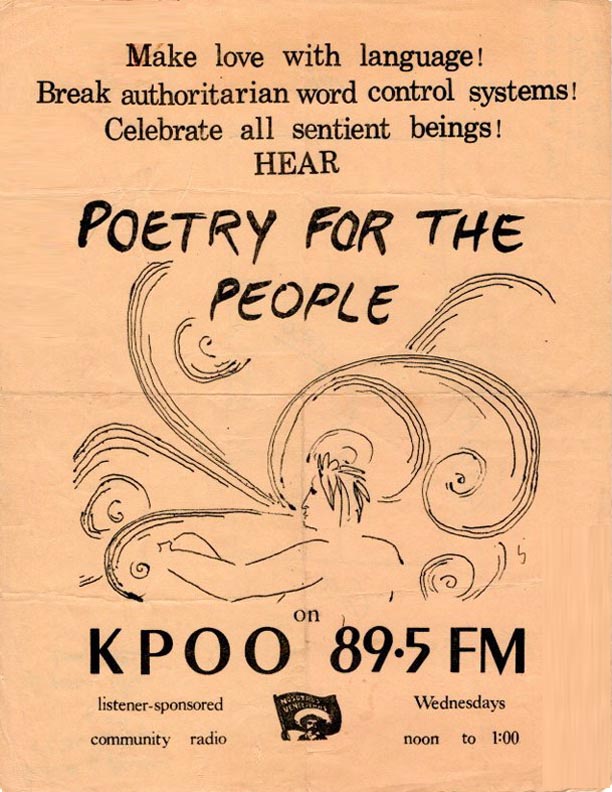

Some of Leslie’s students arranged for a weekly hour-long radio show on KPOO, which in 1978 Kush, Royal Kent, and I took over. None of us had done much radio until then. At that time you needed to pass a test for a Third Class FCC permit to be a host on a low power radio station. We pulled it together and took turns producing shows and being tech. We had a great time with the show for maybe a year and a half, until the station was overhauling their schedule, and we decided to move on.

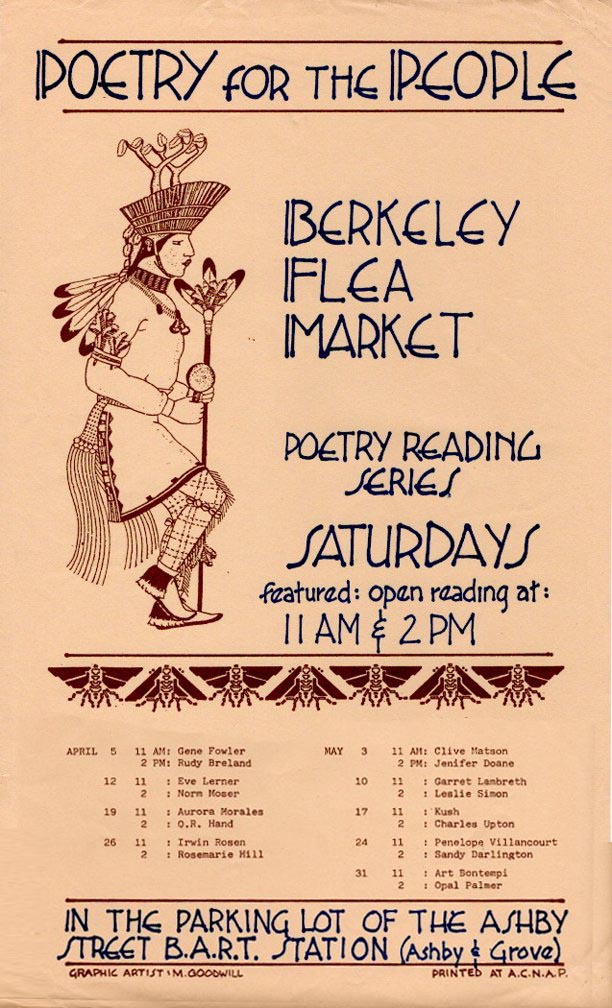

I also organized and hosted a weekly featured/open poetry reading series under the PFTP banner at the Berkeley Flea Market.

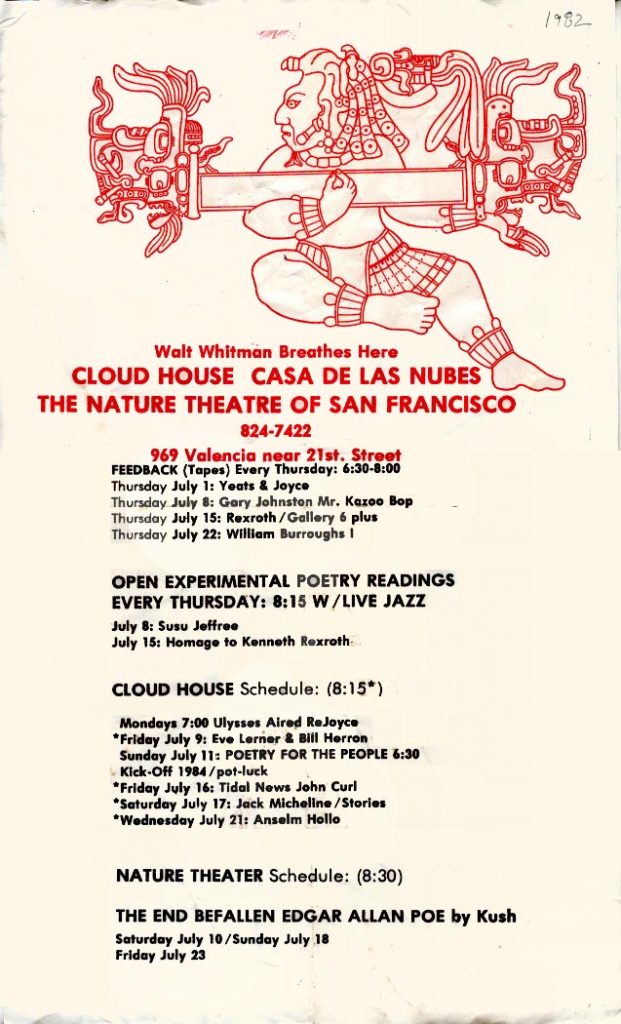

CLOUD HOUSE

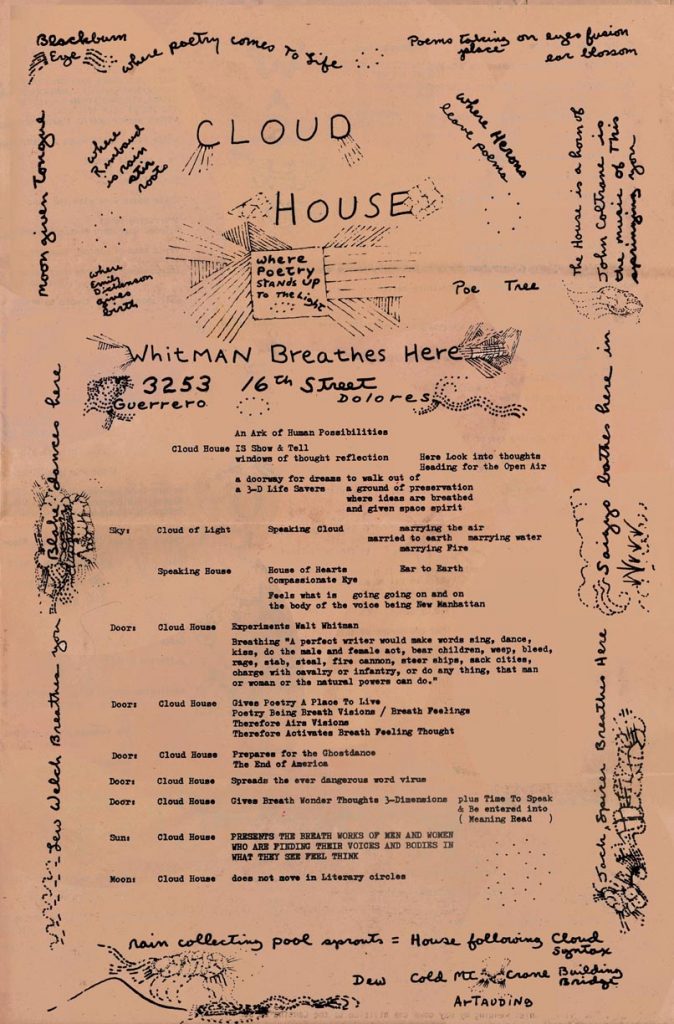

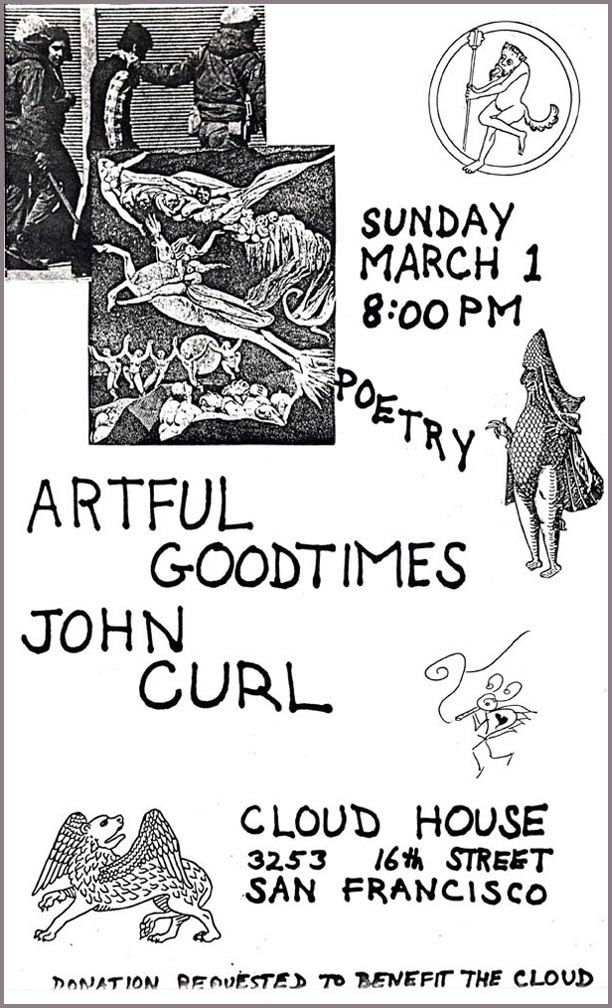

Kush founded Cloud House, “where poetry stands up to the light,” in 1977, a neighborhood poetry center in a storefront on 16th Street not far from Mission Dolores. The sign outside read, “Walt Whitman Breathes Here.” The walls were filled with art and poetry. There were also boxes and file cabinets of poetry archives everywhere. Every Thursday night was an open reading by kerosene lanterns with everyone in a circle on the carpeted floor, sharing a pot of tea and burning sage. Everyone was welcome to read in an atmosphere of total acceptance. In the first round, everyone read one poem; in the second round you could read as long as you liked. It went round and round until no one had any more poems they wanted to share. Kush also read and chanted poetry outdoors around the city and Cloud House launched a series of weekly open-air readings in public places. Cloud House was a welcoming home and community for the poetry I was writing and that I wanted to create.

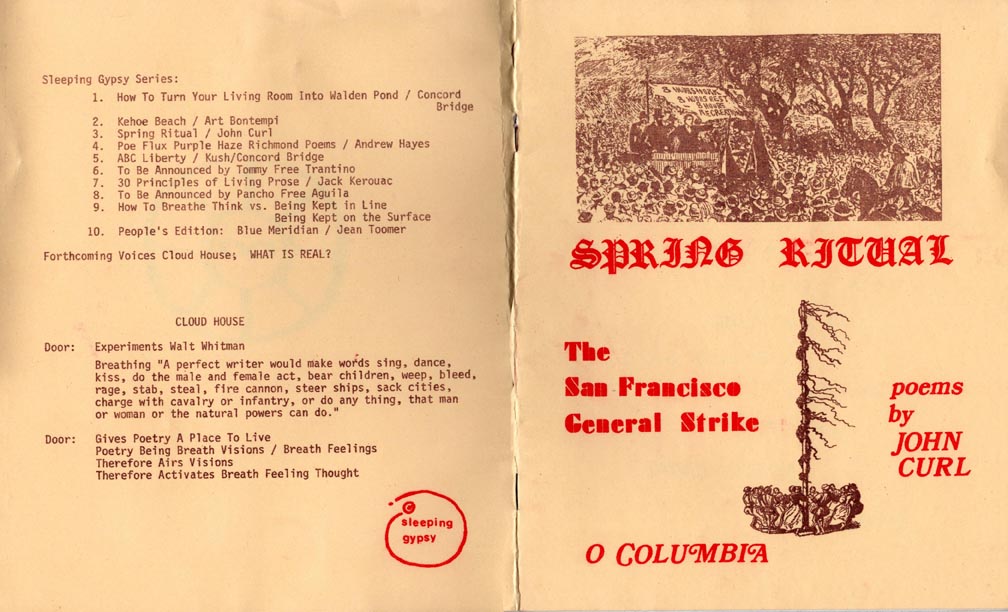

In its first year Cloud House began publishing a series of chapbooks called the Sleeping Gypsy Series. It began with a work by Kush, then one by Art Goodtimes. I published the third chapbook in the series, Spring Ritual (1978), which included my poems O Columbia and The San Francisco General Strike (which eventually became a YouTube video).

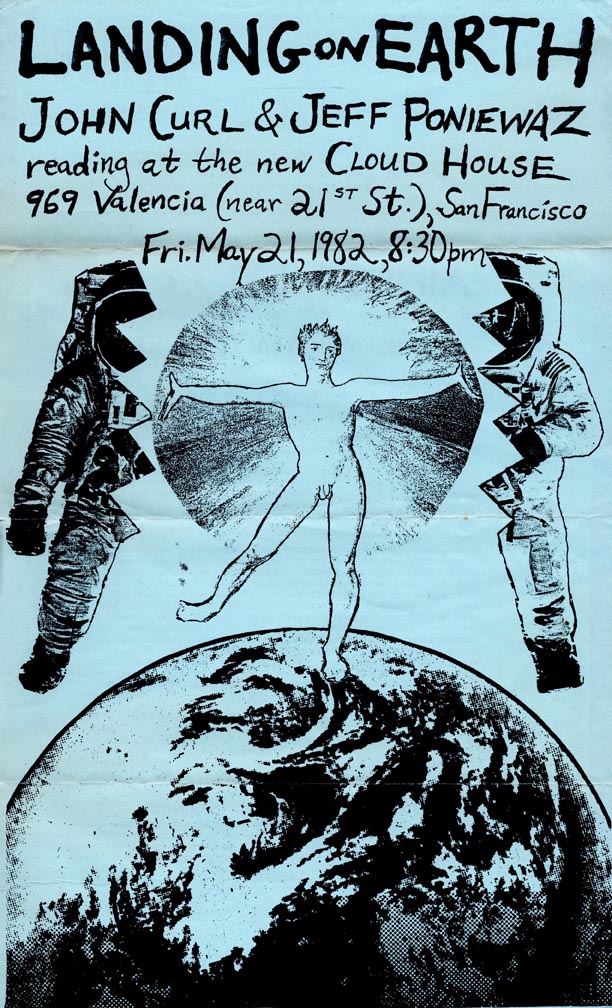

Cloud House also published several extraordinary anthologies, including Blake Times and What is Real? Over the years, a community of maybe forty or fifty poets associated with Cloud House, many of them doing work on a high level. Kush was the centrifugal axis, and his sorcerer’s cape was an umbrella for countless acts and dreams. You never knew who was going to show up on Thursday night. That was where I first met Bob Kaufman, QR Hand, Jack Micheline, Gregory Corso, SuSu Jeffrey, Art Goodtimes. Hirschman used to come there sometimes, often with Mueller or Neeli. Jack would give away stacks of poem-drawings he’d made in crayon and chalk. In the circle were Janet Canon, Phil Deal, Robyn Hunt, David Moe, Andrew Hayes, Jeff Poniewaz, Antler, Garrett Lambrev, Allen Cohen, and numerous others.

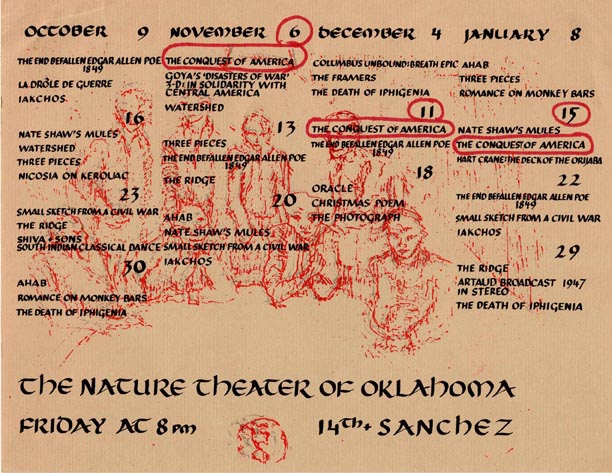

In the fall of 1981, in a new location (having been pushed out by gentrification), Cloud House launched what Kush called the Nature Theater of Oklahoma, a weekly series of plays and performances by a host of authors. It included his own play, The End Befallen Edgar Allen Poe. I had just written a play, an historical drama about Christopher Columbus and the tragedy that he enacted in the Caribbean. With Bill Herron as director and poets and friends as actors, we performed a staged reading. It ran once a month for three months. Kush played the great Taino leader Caonabó, Dennis Dunn played Columbus, my old friend Fernando Barriero from TRA magazine played Commander Bobadilla, and I played a bad friar. The Conquest of America was an early version of The Trial of Columbus, which PEN Oakland staged again three decades later. This play was the first of my writings about the earliest European attacks on Indigenous America, led by Columbus. In the following years I would publish a short epic poem, Columbus in the Bay of Pigs (1988, 1991), a video, The Columbus Invasion (1991), and a documentary history, Indigenous Peoples Day (2017), all with the same focus.

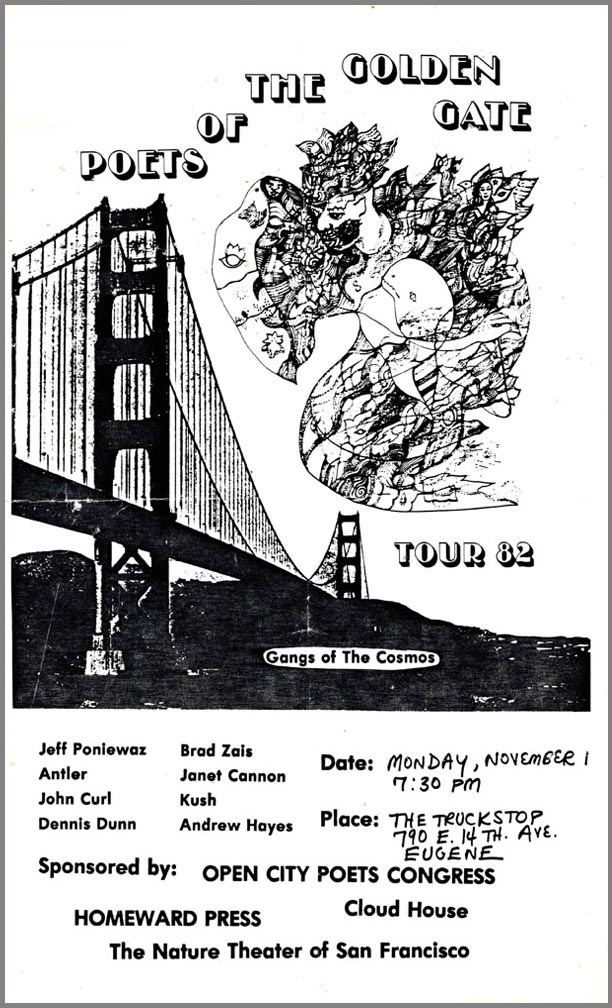

In 1982 I went on two amazing poetry trips with Kush and the Cloud House group of poets. On the first trip I read poetry and sipped tea with Gary Snyder on his land in the Sierra Nevadas. The second was the Poets of the Golden Gate tour up to Oregon, with another incredible group of poets, including Jeff Poniewaz, Antler, Dennis Dunn, Janet Cannon, and Andrew Hayes. I don’t recall all the places we read, but the highlight was certainly when we had dinner with Ken Kesey at his house in the woods outside of Eugene. His old bus Further was still sitting in his yard overgrown with weeds all around it, but would be soon on its way to the Smithsonian. Kesey had just returned from a trip, and all his extended family were there for a big dinner, with him as host and paterfamilias carving the birds. It was all storybook until one poet in our group either had a bipolar mood swing or drank to much of something or both, and began challenging and ragging him, for no apparent reason. Kesey, a big guy and once a college wrestler, jumped up. The poet realized his mistake too late, knocked over his chair trying to get up, wheeled and took off in alarm out the door, with Kesey following after him into the night forest. They left the door swinging open behind them, and everyone with dropped jaws. Luckily they worked it out and came back ten minutes later smiling. That poet tour reminded me of the scene from One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest where McMurphy steals a school bus, escapes with some inmates, and they all go fishing.

UNION OF STREET POETS

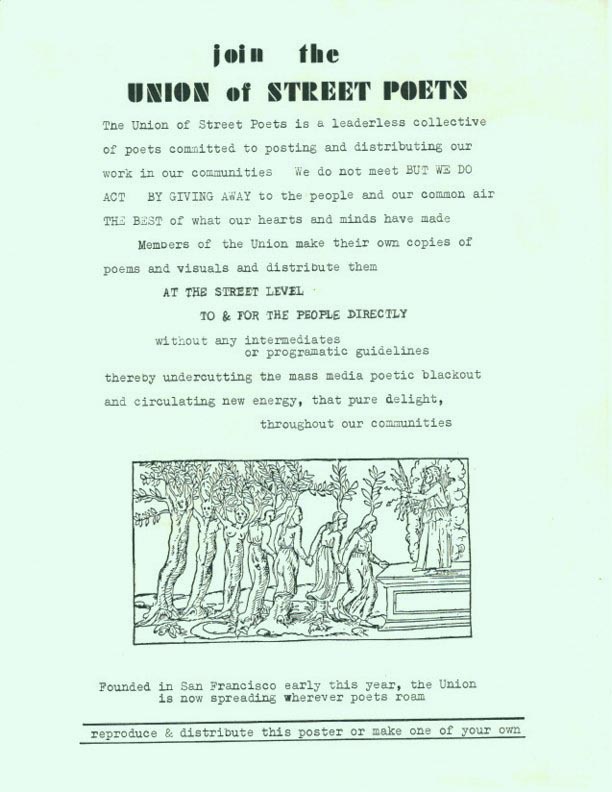

The Union of Street Poets (USP) was simply a concept that sprang from the minds of John Mueller and Jack Hirschman around 1980, an organization that by definition acted but never met, not even once. Any poet could use its name on a broadside or however they wanted to use it, and many poets, including myself, issued broadsides with its logo. The USP defined itself as “a leaderless collective of poets committed to posting and distributing our work in our communities. We do not meet but we do act, by giving away to the peoples and our common air the best of what our hearts and minds have made.” Since the USP only ever existed when poets signed it to their works, in a strange way it remains timeless and eternal.

UNION OF LEFT WRITERS

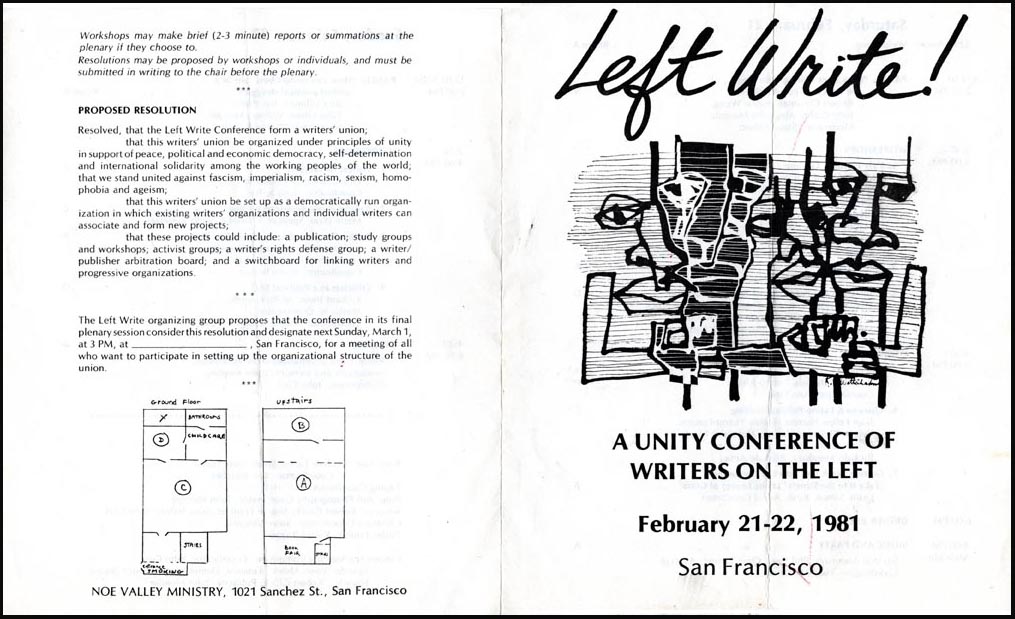

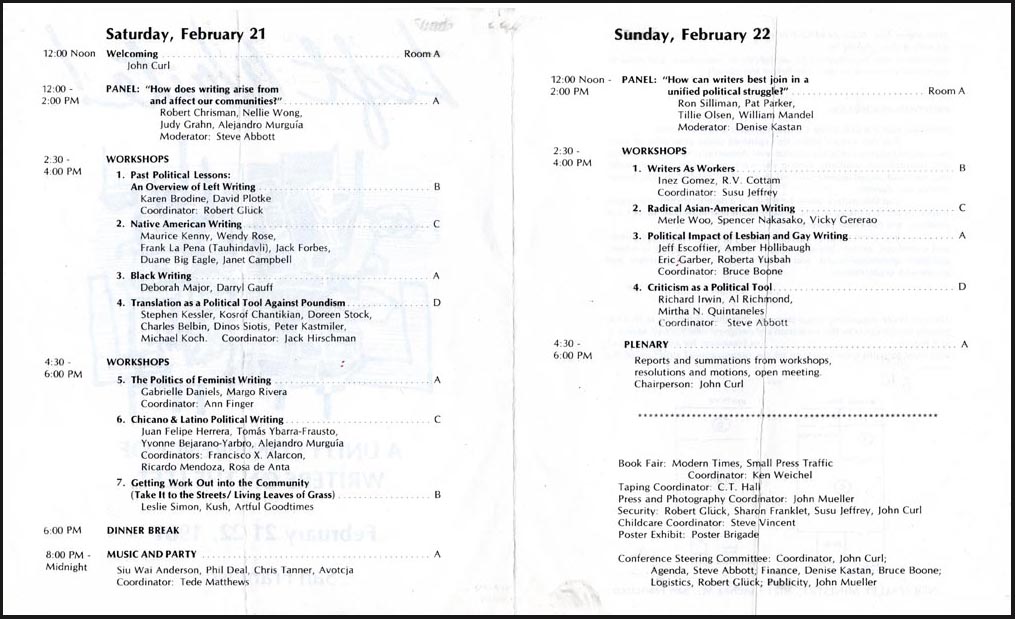

In 1980, while Ronald Reagan was campaigning for president, Steve Abbott and Bruce Boone conceived the idea of a conference about politics and writers and sent out a call to solicit feedback. I met with them, Denise Kasten, Ann Finger, and Robert Glück in the back room of Small Press traffic in July and set up a larger open meeting two months later to plan the conference. About thirty people came to the planning meeting, and I was elected conference coordinator. We agreed on the name Left Write, which was proposed by Jack Hirschman. The conference was planned for a weekend, February 21-22 1981, after the presidential election that would inaugurate the dreaded Reagan era. Starting in October we broke into committees and met regularly. The purpose of the conference was to bring the diverse multi-cultural community together, hold workshops and panels to share our experiences, deepen our understandings and commitments, and hopefully develop an ongoing progressive writers’ organization or alliance.

Over 300 people packed into the Noe Valley Ministry for a triumphant two days during a time of crisis. A glance at the program shows that it was a virtual who’s-who of the progressive Bay Area poetry and writing community. My job as conference coordinator was to set it all in motion with a welcoming, ascertain that the workshops were functioning as planned, and to chair the plenary at the end. I made the rounds of all the workshops, and every one made unique contributions. At the plenary, we unanimously passed the main resolution, to form a Union of Left Writers (ULW) as an umbrella for many activities. We all left the conference energized.

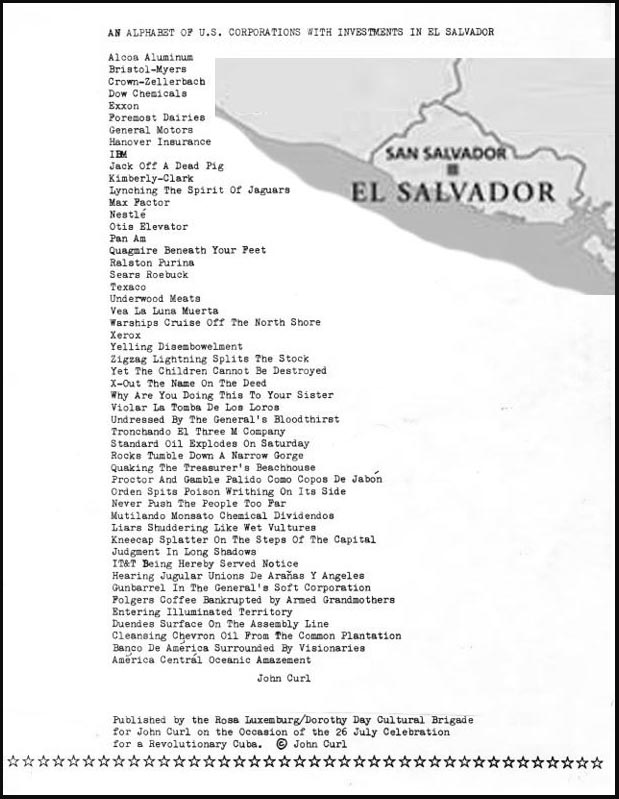

The first few meetings of the Union of Left Writers maintained that high energy. Steve Abbott prepared to publish the workshop reports from the conference; we did benefit readings for El Salvador and the Coalition Against Infant Mortality; the ULW Translation Committee, with Jack as one of the navigators, put out the first issue of a projected regular magazine of translations, Compages.

But we soon realized that we had formed an organization with a serious contradiction. We were trying to be both a membership organization of individual writers and a coalition of existing writers’ organizations at the same time. Some people who came to meetings were treating it as one, and some people were treating it as the other. These required two very different structures; we couldn’t be both at the same time. We set up a committee to work on a new founding document to resolve that issue, and we formed a temporary steering committee to guide the organization asap into a new structure. I continued as chair.

But over the next months many of the schisms historically dividing the American left surfaced, resurfaced, and played out. Meetings bogged down in frustration. Some of these differences, or at least the people representing them, were intransigent. There really were no good guys or bad guys as the dreams of the ULW faded away.

AFTERWORD

Today in 2021, Leslie Simon’s Poetry for the People still continues at CCSF; Kush’s Cloud House continues in Catskill, NY; the Union of Street Poets continues in our imagination. I’ve belonged to other poets and writers groups since, particularly PEN Oakland and the Revolutionary Poets Brigade, but those are other stories.

MY POETRY BROADSIDES, c. 1977-’82

Here is my collection of over fifty poetry broadsides that I published in those years under the banners of Poetry for the People, Cloud House, and the Union of Street Poets, along with flyers and other memorabilia from the time.

0 Comments