INDUSTRIAL COUNTERCULTURE

I arrived Berkeley in 1971, and found a small place in a housing co-op on Channing Way, in a little addition behind the main house. It was perfect for us, a family of three. I made contact with a construction collective called Build, and through them I met other guys who wanted to do jobs together cooperatively. We needed a scaffold for a job, and Vern knew a place where we could borrow one, Bay High, an alternative high school that taught trades to kids who had not thrived in public school. It had been started in 1970, funded in part by a grant from The Whole Earth Catalog (whose founder Stewart Brand, used to regularly visit us at Drop City). The school was structured as a typical “free school” of the era, with few academic demands, and ran an auto repair shop, a print shop, and a woodshop out of a large warehouse in West Berkeley near Gilman Street.

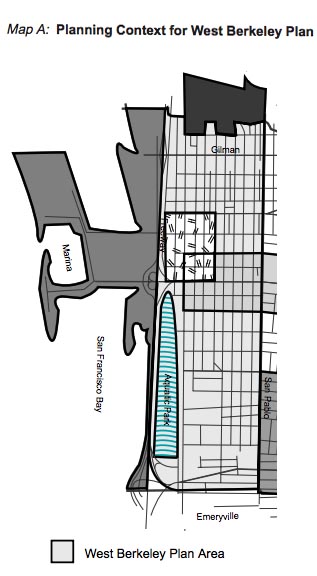

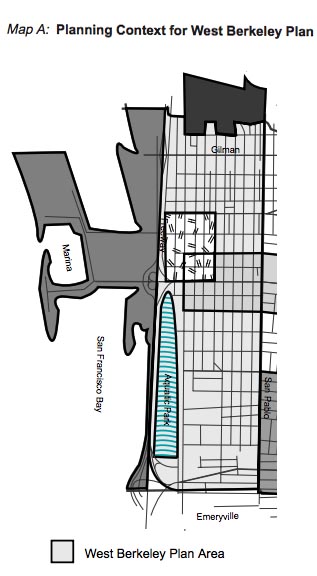

West Berkeley is at the other end of town from the university, and forms part of an industrial belt that has circled the bay since the gold rush. It started out as a working class town called Ocean View before the university was founded, with a distinct history. Its location, directly across from the Golden Gate, resulted in cargo coming from the east to San Francisco being loaded on barges there and floated across the bay. The industrial town grew up around the dock, then over time became part of the industrial belt around the entire bay waterfront.

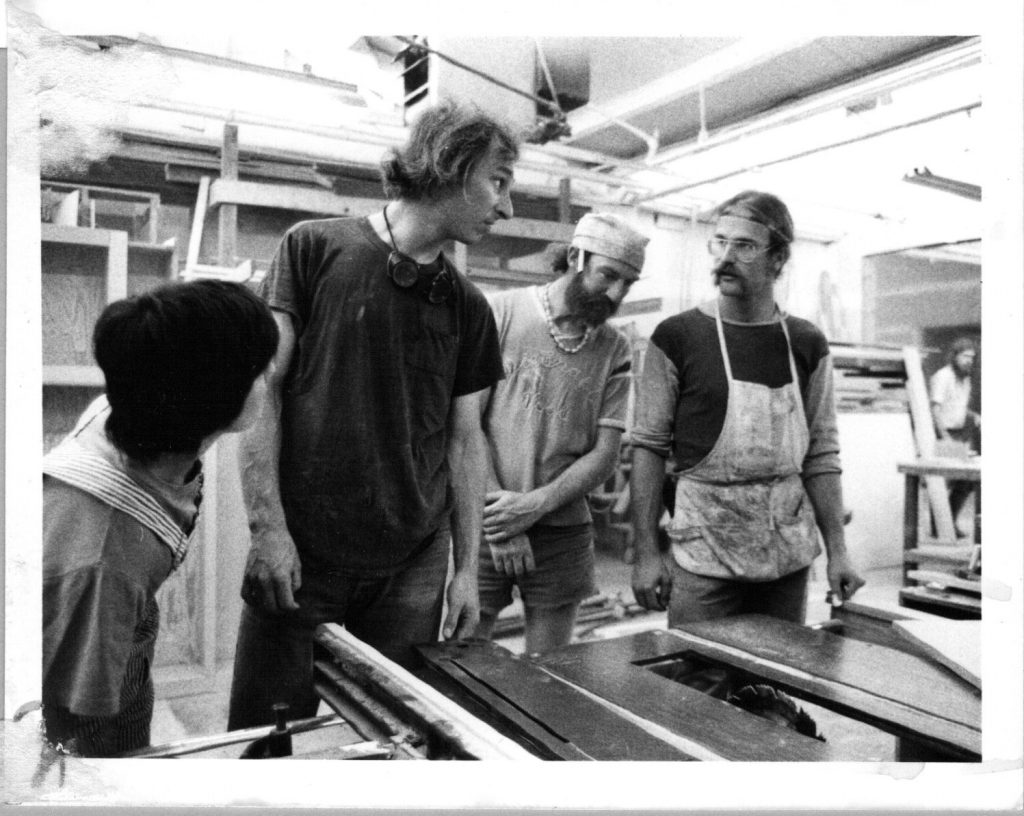

Bay High loaned us the scaffold, but they were going through an internal crisis. The school was nominally structured as a democratic collective with everyone having an equal voice, but a sharp struggle had developed between shop workers and administrators/academic teachers, over the refusal by the administrators to sweep the floor and take out the garbage. Class struggle. The shop workers took over the school, dismissed the administrators, disbanded the school proper, and invited me to join, which I did. Shortly after I joined, we reorganized as Bay Warehouse Collective.

Those were heady times. We felt like the workers had seized the means of production and now we had the power to reshape our world. We held meetings almost daily. Eric made what he called an ostrakon, which in ancient Greece was a potsherd used as a ballot on which people wrote their votes, but at Bay was a carved wand decorated with feathers and leather, which was passed from speaker to speaker so only one person could speak at a time. Meetings would go on until everybody was satisfied, or at least tired of talking. We made decisions by consensus, which usually worked out fine, although it took time, and we paid ourselves salaries according to need, which was very problematic.

At our height, around 35 people worked in the three main shops, plus we also had other operations in the warehouse: a pottery shop, an electronics shop, a typesetting group, a photographer’s darkroom, a legal collective, a candle factory, a food buying co-op, a worm farm, and a theater troupe.

At Bay is where I first really started to learn woodworking. No one had a lot of experience, and we all shared our skills and helped each other. Bay Warehouse Collective was a great place for two years.

But gentrification started to sweep through the industrial areas in the 1970s, and Bay Warehouse was one of the early casualties. The landlord almost doubled our rent because they realized that they could get a lot more if they converted it to offices. At that time there were almost no zoning restrictions in the industrial parts of West Berkeley. It was almost all one big Manufacturing or “M” zone, the base of a pyramid of zoning restrictions, with almost no restrictions at the bottom, where property owners could do pretty much anything they wanted to do. Since rent for office, commercial, and residence was much higher than for manufacturing, landlords were beginning to convert industrial buildings, and in the process pushing out small industries and arts and crafts.

We couldn’t continue at that rent level, so Bay Warehouse folded towards the end of 1973. Each of the three main shops decided to continue separately, to relocate as collective businesses with new identities. The print shop became Inkworks; the auto shop became Car World; the woodshop became Heartwood Cooperative Woodshop, where I continued to work.

I TAKE AN OATH

Being forced to relocate was a big setback and very costly. I promised myself that if this happened again, if gentrification followed the woodshop to our new location, I wouldn’t just roll over and relocate again, but I would fight back.

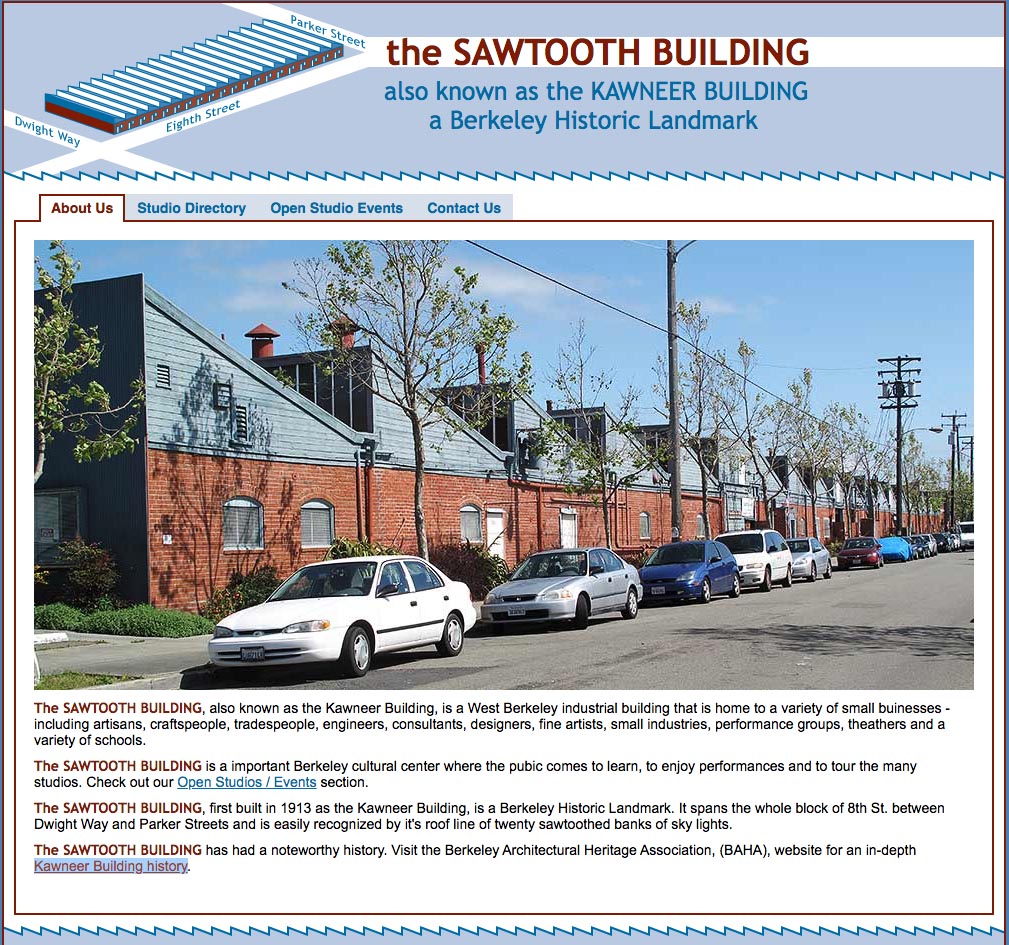

We found a new space in a large brick warehouse that had been the Seely Mattress factory, but was now being subdivided into artisan and artist studios. It would eventually become known as the Sawtooth Building, and was already well known to the architectural community as the Kawneer Building, but at this time neither of those names was in common use. Over the next decade, Heartwood thrived, and the warehouse filled with craftspeople, artists, dancers, and many other cultural activities.

During this period, my main political activities were with the Intercollective, an organization promoting mutual aid and solidarity among collectives and cooperatives. The collective structure of direct democracy, the antithesis of hierarchy, represented our countercultural vision of liberating work and society. We organized conferences and events, and published a Directory of Collectives.

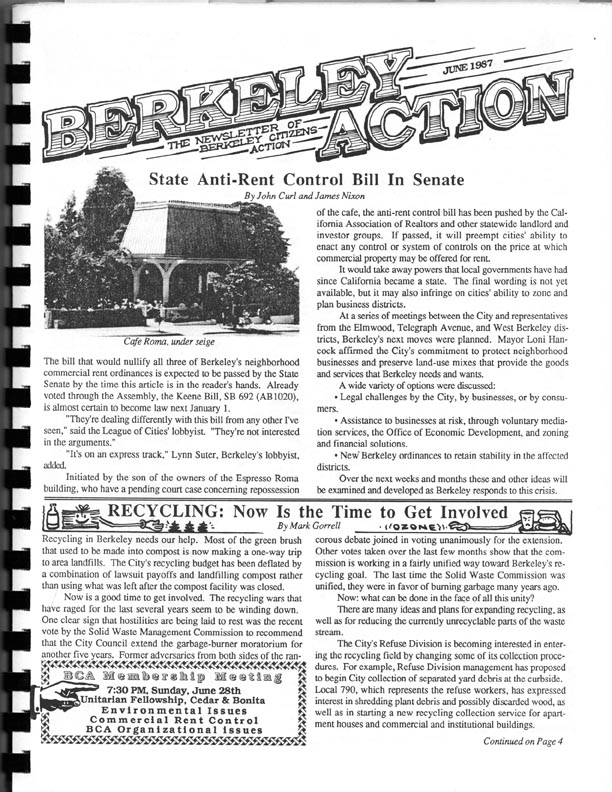

I also worked some with Berkeley Citizens Action (BCA), the progressive electoral coalition first formed in 1974, a kind of local political party, which was just then coming into power. I mostly worked as a volunteer walking precincts to get out the vote. The most burning local issue, aside from the Vietnam war, was rent control, because gentrification was rapidly transforming the demographics of Berkeley, forming an existential threat to the progressive community. The city was becoming unaffordable for people at our economic level. In 1979 “Gus” Newport was elected mayor, and in the following years BCA had its first chance to govern. BCA was one of the most successful local political parties in the country, with a radical agenda.

Two activists who were working with Mayor Newport to promote cooperatives and collectivity, used to come to InterCollective meetings and encouraged us to get involved and help shape city policies. They asked me to a meeting, and the BCA steering committee invited me to join. So I became a member of the BCA steering committee, with the motivation of being a voice for West Berkeley and connecting with allies in city politics and government. We used to meet at the Long Haul on Shattuck Avenue. At that time, no one else active in BCA had a personal connection with the West Berkeley industrial zone, so it wasn’t much on their radar. A few years later I would become editor of the BCA newsletter, where I posted updates about the issues in West Berkeley, and for a while I was co-chair of the steering committee.

WEST BERKELEY TOUR

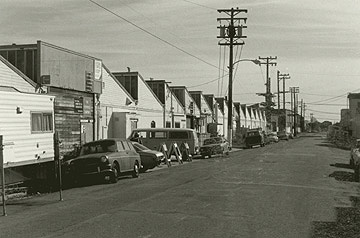

Drive the streets of West Berkeley and you’ll see old warehouses interspersed with residences. Unlike retail corridors, where the storefronts display their wares and beckon to the passerby to stop and enter, the industrial areas are internal, and the buildings usually don’t advertise their identities, except by a small sign or plaque. Yet inside out of view are some of the most extraordinarily creative spaces in Berkeley, a town known for its creative spaces.

Inside of some of those plain warehouse walls are potters, woodworkers, glass blowers, artists, craftspeople, dancers, small manufacturers of every description, you name it. This is the only place in Berkeley where these kinds of things are not only still possible but thriving. This is the light industrial zone, where people get dirty hands and real stuff is made. It is a section of the old industrial corridor that once encircled San Francisco Bay. The smoke stack industries began leaving in the decades after World War Two, and many the warehouses were torn down or subdivided and converted to other uses. But while in some other parts of the Bay Area, the old industrial zone was gentrified into upscale offices, stores, and residences, in Berkeley however, much of the industrial space is still there today, preserved for small industries and arts and crafts by mixed-use zoning. That has resulted in the dynamic neighborhood West Berkeley remains today, where diverse activities are maintained in a wide range of economic levels.

The unique reason why the dynamism of West Berkeley has not succumbed the loss of diversity brought about by gentrification, is the West Berkeley Plan.

THE SAWTOOTH BUILDING

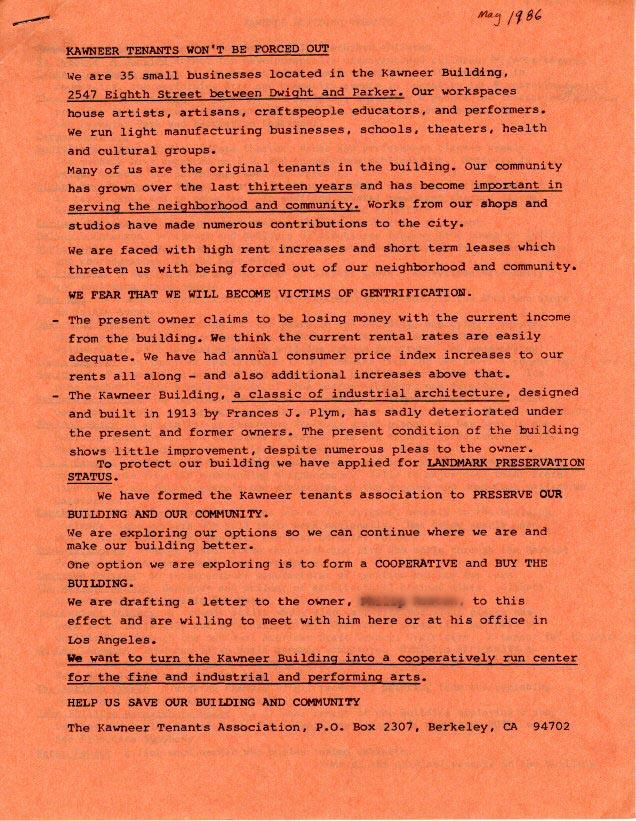

In 1985 the Sawtooth Building, where my shop Heartwood had relocated a decade earlier, was sold, and the following year a new property management company took over. Soon after, a notice appeared on everybody’s door that they were “improving and upgrading” the building, converting some of the arts and crafts and industrial spaces into offices, and there would be rent increases for all.

This was exactly what I had been fearing ever since my shop had been forced out of Bay Warehouse a decade earlier, and I already knew that I would do everything in my power this time to fight back.

Everybody in the building was alarmed and the halls filled with people talking about it. Lynn of Quicksilver Pottery offered her studio for an all-building tenants meeting; we made a flyer and spread the word door to door. Almost everybody showed up and packed into her space. At that time the artisans, artists, craft manufacturers, dancers and self-healing instructors in the building mostly only knew each other casually, from sharing the halls and truck doors, borrowing a tool, or bumping into each other at the communal sinks. We quickly formed a tenants association to fight back, consulted a lawyer, and notified the management company that we would not negotiate with them one by one as leases expired, but we all would negotiate together through collective bargaining. At the same time, we made an offer to the owner to buy the building and turn it into an arts and crafts cooperative. Through several letters and communications, our lawyer was quickly in a semi-serious discussion with the owner over the selling price.

LIFE ON MAARS

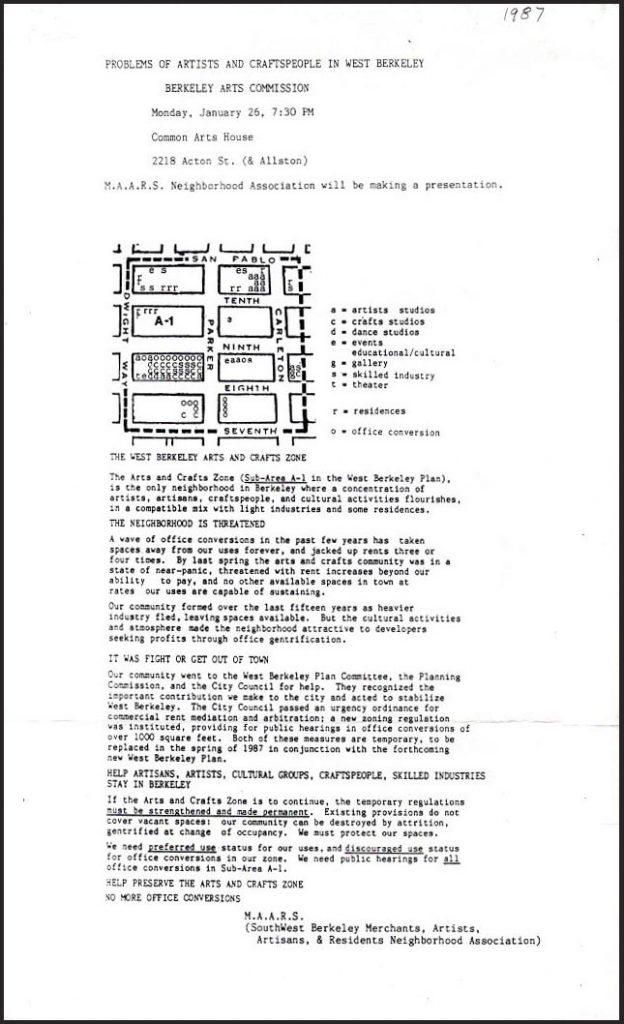

We were not the only building of arts and industries under threat. Not far away, a very public struggle had been taking place for the past year, since 1984, between tenants of the Durkee Building, formerly a canning company, and Wareham, a developer who wanted to evict the artists and industries and convert the building into offices and labs. A few blocks away Nexus, another artist and artisan building, also founded by people from Bay Warehouse, was under a similar threat. Several neighborhood businesses and residents became alarmed and formed MAARS (Merchants, Artists, Artisans, and Residents), a grass-roots community group to support the Durkee tenants fighting eviction and to lobby the city to intervene and stabilize the neighborhood. One of the central organizers of MAARS was Rick Auerbach, a resident of a small house nearby. Rick was to become a key person in conceiving and writing the West Berkeley Plan.

I already had connections with city hall through BCA, and knew various politicians and activists. I went to Mayor Gus Newport’s office, explained the situation, and arranged for Vice-mayor Veronika Fukson, Councilmember Wesley Hester, and candidate Carl Jaramillo to come down to the warehouse and see the situation on the ground. Then potter Lynn Turner and I organized the tenants to meet them in one of the warehouse bays. We toured them around the labyrinthine Sawtooth building and explained the problems. They all vowed to help.

Rick Auerbach heard about what was happening in the Sawtooth Building, and came to some of our tenants meetings. He was the only outsider we let in. He had been working with Leslie Emmington from the Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association (BAHA) to designate the Durkee Building a landmark, making it much harder to tear down. Rick and Leslie proposed that we do the same with the Sawtooth Building. Leslie showed me a newspaper article about our building’s history from the Berkeley Gazette a few years previously, with an early photo of the warehouse with a cow in a field behind it. “Kawneer – the product that became a building.” She gave me a landmark application, and explained how to walk it through the Landmarks Commission and the city council. I proceeded to write the application and we proceeded to landmark the building.

Meanwhile, the City Council acted to stabilize the neighborhood by initiating the West Berkeley Plan process.

THE WEST BERKELEY PLAN

At the root of our problems was that the city had no policies to guide development in the neighborhood. West Berkeley needed an Area Plan. We made the case that arts and crafts and industrial space needed to be recognized as a community resource and protected, because maintaining its existence is a key factor in economic and cultural diversity. Since so many residents and businesses were dissatisfied with the rapid unguided change that was happening and were calling for the city to intervene, the City had to act..

The Berkeley City Council did something almost unheard of in city planning. American cities are standardly planned by professionals, commissioners, and politicians, after the usual public hearings of course.

Instead of doing that, the Berkeley city council embarked on a great experiment in American democracy: can a neighborhood plan itself? Can a complex, diverse neighborhood plan itself? Can people who have no experience in city planning plan themselves?

They set up a process of open community meetings, guided by the planning commission, to write an area plan. The West Berkeley Plan Committee membership was determined by whoever cared to come to these meetings. Membership in the Plan Committee was open to all stakeholders who showed up.

At the beginning I didn’t have any experience in city planning, but I was soon in it up to my neck.

Gil Kelley was the planning director, Carl Anthony was the first chair of the committee, Nathan Landau was the project manager, and Karen Haney-Owens was the Senior Planner.

The Plan Committee meetings, at the West Berkeley Senior Center, were well attended. Chaired by planning commissioner Anthony, the early meetings were punctuated by fiery exchanges between two groups: the developers, realtors, and large property owners on one side, and on our coalition of artists and craftspeople, small manufacturers, and residents on the other side. But there were also other stakeholders with different points of view: environmentalists, labor, the Black clergy, neighborhood groups, the university, recyclers, labs, and others. It took a while until all the different constituencies joined one by one in the process. Over 65 people were members of the Plan Committee.

THE ARBITRATION ORDINANCE

The first order of business was to stabilize the neighborhood. The Plan Committee estimated that it would take nine months for us to write the plan and begin to implement it. We needed a strategy for the interim period.

To stabilize the situation, the City proposed a mild form of commercial rent control, a temporary ordinance that would sunset after nine months or sooner if the new plan came into effect sooner. Berkeley was already using commercial rent control to stabilize two retail corridors at the other end of town, both of which had also been damaged by rapid gentrification, the Elmwood and Telegraph Avenue districts. The Elmwood Commercial Rent Stabilization Ordinance had been on the ballot in 1982 and approved by voters by a hefty margin. Commercial rent stabilization was two years later extended to the Telegraph Avenue neighborhood. Both seemed to be working well, so we used those ordinances as models for West Berkeley. Our situation was very different of course, being a manufacturing zone.

After much process, the Plan Committee unanimously made our recommendations to the city council, and in October, 1986, the council passed, as one of the last acts of Mayor Newport’s final term in office, the West Berkeley Interim Commercial Mediation and Arbitration Ordinance, an urgency ordinance for the manufacturing and industrial districts, establishing commercial rent and lease term mediation and arbitration, with a cap of 5% for annual rent increases and just cause for eviction.

In the Sawtooth/Kawneer Building, leases were regularly expiring one by one. Now when a studio received a new lease proposal from the management company, the tenant would bring it to the tenants’ association. We would read each other’s leases and compare them. The management company wanted to prevent us from comparing leases and tried to put us in competition by telling each one that they were getting a special secret deal. When the management company tried to insert an illegal clause into a lease, we quoted the Arbitration Ordinance to them.

But just four months later, a bill was introduced in the state senate in Sacramento, written by the real estate lobby, to preempt all California cities from enacting any commercial rent control. They wanted to nip our example in the bud before it had a chance to spread.

In June, 1987, Councilmember Nancy Skinner led a delegation of Berkeley business owners to Sacramento to lobby against Senate Bill 692 and in favor of commercial rent stabilization. I spoke at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing, but the senators turned a deaf ear. By autumn of that year our Arbitration Ordinance was null and void, and commercial rent stabilization was effectively eliminated as a tool for California municipalities to maintain affordable commercial areas.

We were back to square one, badly bruised. In the Sawtooth Building, the management company let us know that they were well aware that the Arbitration Ordinance was now defunct, and in the next leases that were up for renewal, they demanded for a 33% increase instead of the 5% cap.

LONI TAKES THE REINS

Meanwhile, in 1986 Loni Hancock had become the city’s first woman mayor and the progressives held onto a council majority. One of the first of many pressing issues she took on was the West Berkeley Plan.

She had campaigned as a problem solver; her instinct was to bring people together. She promoted the concept, Think Globally, Act Locally; her motto was win-win. Delegations from our group met with her and various councilmembers, including Maudelle Shirek and Nancy Skinner.

As a member of the BCA steering committee, I had an inside view of the process at city hall. A “packet” meeting, where the allied elected officials discussed the agenda items, was always held a couple of days before an upcoming council meeting. I had a standing invitation to attend and participate in these packet meetings, so when any issue related to West Berkeley was on the agenda, I would sit in and contribute my perspective.

THE ARTS AND CRAFTS ORDINANCE

Our allies in city government assured us that there were other approaches to addressing the immediate threats to affordable art and industrial space; we didn’t need to wait until the entire new plan was written and in place. Arts and crafts could be protected through zoning regulations, which could be passed at any time.

So we began work on the Arts and Crafts Ordinance. The Plan Committee unanimously passed our draft to the planning commission, and it sailed through the city council in 1989. The new ordinance declared arts, crafts, dance, music, performance theaters, and art galleries to be Protected Uses; studios currently in any of those uses had to remain in one of those uses. A studio could change to a different protected use, but not to any unprotected use. The idea was that all arts and crafts uses support a similar level of rent, and therefore are not a threat to displace each other. The landlord had to accept an affordable rent level, or the studio would be empty. The new arts and crafts zoning became the first foundation block in the West Berkeley Plan.

With the city no longer facilitating conversions, and with our tenants association at the Sawtooth Building causing the management company problems at every turn, the predatory manager was soon gone, and the old manager was back. The Sawtooth Building ownership changed hands again, and we were very fortunate to wind up with a building owner who was happy to abide by the arts and crafts protections and maintain a block full of creative tenants paying sustainably modest rents.

THE PLAN COMPLETED

The city council then directed the Plan Committee to examine the idea of expanding that concept of protected uses to industrial sanctuaries.

We had originally expected the Plan process to take nine months, but it took a lot longer to resolve the many issues involved with rezoning a neighborhood as complex as West Berkeley. Over time all the stakeholders came to Plan meetings and had their say, so in the end all of West Berkeley was well represented. At those meetings, as we got to know our allies and opponents, we came to understand each other’s positions better and how the system works. Over time the Plan Committee all agreed to find accommodations that we all could live with, so that all sectors could continue to thrive, and West Berkeley could grow and develop in organic ways, together, without pushing any of us out of town.

With that in mind, we divided West Berkeley into a number of districts, based on their existing uses. Like arts and crafts studios, manufacturing uses would be declared protected uses, and industrial spaces could only be reused by other industries. The zones with more industry would remain that way, and the zones with more residents would also remain that way.

In the end all the many constituencies signed off on the final Plan, unanimously. The process wound up taking eight years. In 1993 the City Council, with the leadership of Mayor Hancock, passed the West Berkeley Plan unanimously, and it became City policy.

IMPLEMENTATION AND REALITY

After that it was time to write the zoning ordinances that would implement the plan. The devil was in the details of course, and these were the details. The city planners worked closely with a number of us from the different constituencies, including Rick Auerbach, Laurie Bright, and myself, for five more years until, in 1998 the City finally rezoned West Berkeley along the lines laid out in the Plan.

But the ink was hardly dry before some developers and property owners began lobbying to end the industrial protections. In the following years, the City’s implementation was spotty. Developers found loopholes in the provisions, and several industrial buildings were somehow converted into offices.

Meanwhile the dot.com explosion triggered an office boom around the Bay. Many building owners in West Berkeley wanted to convert and cash in, but were limited by the Plan. Then when the dot.com bubble burst in 2000, acres of empty office buildings littered some parts of the Bay Area, but not Berkeley. The Plan’s industrial protections kept Berkeley’s diverse economy comparatively stable; arts and crafts maintained their places in the dynamic West Berkeley mix; the neighborhood maintained its character and relative affordability.

WEBAIC

Shortly after approving the West Berkeley Plan in 1993, the City recognized that the industrial and artisan/arts community needed an organized voice, and initiated WEBAIC (West Berkeley Artisans and Industrial Companies). With Rick Auerbach as staff, WEBAIC campaigned in support of an affordable, sustainable industrial and arts economy and culture in West Berkeley, and continues to do so today.

THE WEST BERKELEY PROJECT AND MEASURE T

When Loni’s husband Tom Bates was running for mayor in 2002, I drove around with him, showing him West Berkeley, but the industrial zone was foreign territory to him. I was hoping that our community would have a seat at his table, but I was very wrong. Under his new administration, the doors were wide open to developers and to the university, but never once did he invite us inside to participate in the discussions. Tom was always on the conservative fringe of BCA. I think the reason that he got away with so much, was because a lot of people cut him slack because of Loni.

From the beginning of his first term he supported loosening up the regulations of the West Berkeley Plan and encouraged more and larger developments. This continued as he grew powerful over his twelve years as mayor. Tom wanted to make his mark on Berkeley by transforming it with large development projects, and his primary target at first was downtown.

But Bates saved his legacy project as a climax at the end of his stint. He called it the West Berkeley Project.

Despite the similar name, the West Berkeley Project was the opposite of the West Berkeley Plan, and maybe the confusion was intentional. It seemed to start out innocent enough. In 2007, the City Council asked the Planning Commission to recommend zoning amendments for West Berkeley “to ease the obstacles that people face when trying to build, operate, or grow industrial businesses in West Berkeley. The work program seeks incremental changes to the zoning ordinance, not wholesale changes to the West Berkeley Plan.” Over the next five years, planning staff spent large amounts of time and resources on the West Berkeley Project. It eventually boiled down to a proposal to allow developments of offices and apartments “on up to six large sites,” over the next ten years, with 75-foot high 6-story buildings encompassing around 50 city blocks.

A strong outpouring of opposition from the West Berkeley community met the proposal at every public hearing. Wary of the flack, the mayor and city council at the last minute avoided voting by putting it on the ballot for the voters of Berkeley to decide in the 2012 election. The opposition with almost no funds launched a grass roots campaign against it. The well-heeled backers of Measure T paid for large amounts of glossy literature that filled every voter’s mailbox. Many observers thought it was a sure thing. But on election day, November 6, 2012, the people of Berkeley rejected the Project and reaffirmed their support for the West Berkeley Plan.

And that is where we still stand today. West Berkeley remains a dynamic mixed-use area, still affordable to a wide variety of uses at many economic levels, and still helping to keep the city diverse. For that we can thank that miracle of grass roots democratic city planning, the West Berkeley Plan.

0 Comments